I’m proud to announce that my collaboration with PixelLunatic (my wife) for Ludum Dare 44 is released!

Check it out here!

There’s a web version and a Windows version. Let me know what you think!

I’m proud to announce that my collaboration with PixelLunatic (my wife) for Ludum Dare 44 is released!

Check it out here!

There’s a web version and a Windows version. Let me know what you think!

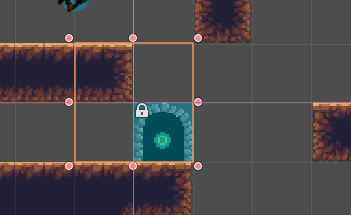

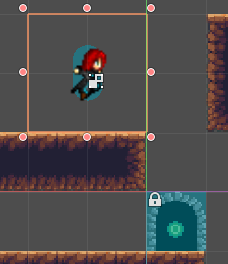

In Godot 3.0, when you create a scene or a node, a 64×64 selection square appears around it by default. You cannot change the size of this selection square, and resizing it changes the scale of the scene/node, rather than resizing it.

It gets particularly annoying when you are trying to place said scene/node instead of a snap-grid, and the 64×64 area not only clashes visually with your grid, it makes it hard to determine where the position actually is! It’s been a source of frustration for me as I learn how to make games using Godot.

The good news it that this seems to be one of the things getting changed for Godot 3.1. While looking to see if there are ways to work around this quirk of Godot, I came across this change being merged into Godot’s master branch: https://github.com/godotengine/godot/pull/17502

Basically, it resizes the selection rectangle to fit the dimensions of a sized child, and in cases where there is no sized child it uses a crosshair centered on the actual spawning position of the entity. This looks like it’ll resolve my gripes with the selection square quite well.

Godot 3.1 is currently in beta, so hopefully this will be released soon! Because the release seems imminent, I’ll just keep putting up with the selection square until 3.1 officially comes out.

Outside my home office window, fluffy flakes of snow drifted down from the night sky, coating the ground in white, hiding the dreary brownish grass. It was a picturesque scene, and I allowed myself a brief moment to enjoy it; but then my focus turned back to the task before me: crafting the finishing touches of a sample game UI. A last practice project, in preparation for the challenging journey I was about to undertake.

In less than an hour, Ludum Dare 43 — a video game competition wherein participants design, develop, and deploy a video game in 72 hours — would begin, and I wanted to be sure my mind was primed and ready to roll the moment the competition began.

Before you continue further, dear reader, let me forewarn you: this is no mere post, simply detailing the development of a video game. This is a tale of hopes and dreams, of fear and despair; a tale of lessons learned, best laid plans, and desperate decisions; perhaps most of all, it is a tale of one man’s journey to stare dread fate in the eye and dare to succeed.

This, then, is the tale of my experience creating Sanity Wars for Ludum Dare 43, in all its horror and glory. Sit down, buckle up, and hold on.

I’d reserved today — November 30th, a Friday — and the following Monday and Tuesday off on PTO, in preparation for this weekend competition. I’d spent nearly a year teaching myself how to create video games, and now was when I felt my skills were sufficiently advanced enough to tackle a real challenge: Ludum Dare, a legendary video game competition where participants are given 72 hours to create a brand-new video game.

Though unconventional, I planned to enter the contest with a custom JavaScript-based engine that I coded myself, from its humble beginnings as a tutorial engine to its current state, with my unique experiments and needs added to it. It was general enough that I felt comfortable putting it to the test in the fires of competition.

This was an important moment for me. One of my dreams has been to create and release a professional video game, and to me this contest felt like the perfect opportunity to test not only my skill, but also my resolve. How would it feel to channel my creative and intellectual effort into making a video game? Would I enjoy the process enough to commit to wanting to make a full-fledged game later on down the road? Could I make a game that people would enjoy playing? Over the next three days, I reckoned, I’d find out the answers to these questions.

At 8 p.m. CDT, the theme for Ludum Dare 43, voted on by its participants, was revealed: “Sacrifices Must Be Made”. I was pleased; this was one of the options I’d been voting for. As a creator, I’ve always been partial to the thematic and narrative drama sacrifice offers, and I knew I’d be able to come up with something that would fit this theme.

Pacing back and forth in my home office to get my creative juices flowing, I hashed through various different possibilities. Eventually, I settled on a general idea for the signature game mechanic: a side-scrolling platformer where the player used a resource called “sanity” to cast spells — but their sanity was also their health bar, and casting too many spells would deplete their sanity below zero, causing the player to die.

Additionally, players would not be able to access these spells at the start of the game; they’d instead start with something called a “sanity buff” which increased sanity recharge rate. If the player chose to sacrifice these buffs, they’d gain access to spells, but also decrease the rate at which their sanity recharged.

The narrative theme I created to support this mechanic was that the player would be fighting a malevolent being named the Dread Overlord, who held the entire world under the sway of terror, and that the player’s narrative goal would be to weaken the Dread Overlord’s iron grip, bringing salvation to the world. In this, the game also served as a loose allegory to the struggle with bipolar disorder, a struggle I am intimately familiar with, and that further endeared me to the idea. It was, I felt, a perfect fit with the sacrificial nature of the theme, as well as the sanity-casting and buff-sacrificing mechanics.

Little did I know of the irony this narrative theme would present later on in the competition.

With my initial planning made, I sat at my desk and immediately began prototyping my sanity-casting mechanic. It so happened that I already had a spell-casting mechanic built from a previous experiment. Using this as a base, I managed to hammer out a working prototype of the mechanic by early morning. The player’s hit points, or HP, would be directly tied to their mana — or, as I was calling it, “sanity”. Spells could not be accessed until their hotkey was held down for a long-enough period of time — aka a “sacrificed” sanity buff. Reducing sanity to below 0 would trigger the player death state, though I had yet to code what that actually looked like.

I also came up with a tentative title for the game: “Sanity Wars”. It wasn’t a perfect title, but I’d spent half an hour brainstorming possible titles, and this was the one that felt the least cheesy. I figured I’d revisit it later and come up with something better, near the end of the competition.

Feeling satisfied with the current state of things, I decided to call it a night and get some sleep. My confidence at this point felt solid; I believed that I had enough time to take this vision I’d come up with and hammer it out. Soon, I was fast asleep.

Around 8-9 a.m. CST, I woke up to a breakfast prepared by my wonderful, amazing wife, and I enjoyed the family meal before returning to the office to begin the day’s work on my game. The first thing I did was to finish implementing player death, which didn’t take much time. I just tied the player HP stat to mirror the sanity level.

Now that I felt I had the “core” of the game implemented, I thought about what to tackle next. I’d noticed the tileset I’d been working with included sloped tiles, but my engine didn’t have support for moving on a sloped tile. So…why not knock that out real quick?

Three hours later, I had a very buggy implementation of slopes; try as I might, I simply could not get the physics of walking on the slope to work correctly. At that point, I finally asked myself the question that I should have asked myself before I started working on slopes: Is this a feature I really need in my game?

The answer was glaringly obvious: No, it did not. I had been developing just fine with block tiles and jumping around, and while I loved the idea of including slopes, they were far from essential for my game to work. Thus…I nixed the idea and moved on. Three hours, down the drain, over a needless feature…

Lesson Learned: Question whether the feature you’re planning to add is necessary before writing code for it.

I decided my next goal should be to implement an enemy. Hitherto, all I had was a player and the sanity mechanic for casting spells. There needed to be at least one enemy, ideally more, for the player to contend with.

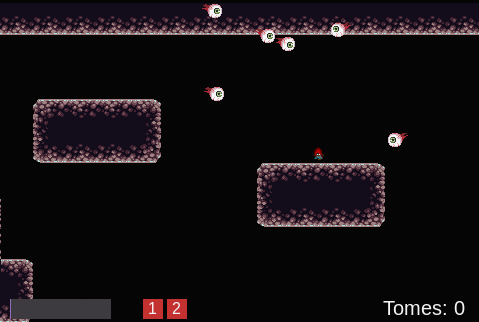

I decided I wanted to create a flying enemy, to avoid having to deal with determining where a ground character could move. After perusing OpenGameArt.com for a considerable period of time, I found a floating eyeball animation that looked delightfully menacing. With that as my art base, I created a floating eyeball entity, which would fly at the player, then back away to a random distance once they got too close, then either wander around for a bit or immediately descend upon the player again. When they were close enough to the player, they would trigger a sanity drain, thus “attacking” the player. It took another few hours, but it was complete and I had it integrated into Tiled (the tilemap editor I was using), so I could place floating eyeballs anywhere I wanted.

By then, the hour was getting late. I took a short break, to ponder my next moves. That was when it finally dawned on me: I had a mechanic, I had a player, I had an enemy…but I had no core game loop. In other words, I had no goal for the player to attain, no objectives to attain along the way. All I had was a map with a sanity caster and a few floating eyeballs. That wasn’t a game, that was a setup.

What was the player’s goal? In order for my game to truly be a game, I needed to answer that question, fast, and then implement the bare minimum necessary to make that goal playable.

Lesson Learned: Hash out the core loop for the game right away. Maybe it will change later, but at least have an initial iteration.

After some brainstorming — I can’t recall exactly how long — I settled on the idea that the player needed to survive and find a Final Exit, but this wouldn’t be considered a true victory unless the player first found some Objective; both the Final Exit and the Objective would be randomly spawned in one of a series of maps. Each map would be connected linearly by portals. I felt these things should all be doable within a day or less, and now that it was past 1 a.m. of the next morning I decided to go to bed now. Hopefully, this would give me the energy needed to bang things out quickly.

The next morning, I woke up, scarfed down a quick breakfast, then headed back into my home office to start implementing the Map Portals mechanic. Up until now, I had been working with isolated test maps. In theory, I should be able to write code which would create two portals on a map, each linking to a different map, as determined by the load order in my map configuration file.

I spontaneously decided that I wanted the player to be spawned randomly as well, and that furthermore I wanted the player to spawn only in a map corner. Thinking that this shouldn’t be too hard, I got to work designing and implementing the code that would let me do this.

It took more work than I thought it would. I not only needed to restrict where on the start map a player could spawn, I also needed to check and make sure the spawn location was actually habitable by the player (in other words, not inside a solid tile, like a wall) and directly above a ground area (so the player wouldn’t spawn at the top of a tall map in mid-air). After several hours, I had the mechanic working, and proceeded to work on the Map Portals.

A lot of the spawning logic I used for the player also applied to spawning Map Portals, so I made use of copy-pasta and removed the map corner restriction. I then needed to add logic to prevent map portals from spawning on top of each other (or the player), as well as logic to prevent portals from spawning too close to each other.

Another several hours later, I had the portal spawns complete. Now, for the challenging part: enabling the player to press a key in front of one of these portals, and be teleported to the correct corresponding portal on the linked map.

It turned out to be even more complicated than I expected. First, I had to set up a system by which two portal objects could be “linked” together so that they’d always send the player to the correct location. Then I had to load the next map’s data into the game while swapping out the old map data (but not deleting it, because I’d need to restore it when the player returned to that map). The player also needed to be teleported to the receiving portal’s coordinates, which involved resetting the camera to focus immediately on the receiving portal’s location and preventing the player from accidentally teleporting back to their original location by holding the action key a fraction of a second too long. There also needed to be logic to determine where the Final Exit would be spawned, and only render the object when the player was on the chosen map. Finally, any additional entities (enemies, the Objective) on one map needed to be removed from the game loop, then put back in when the player returned to that map.

In short, I needed to make maps containing bad guys, portals, tomes, and the exit.

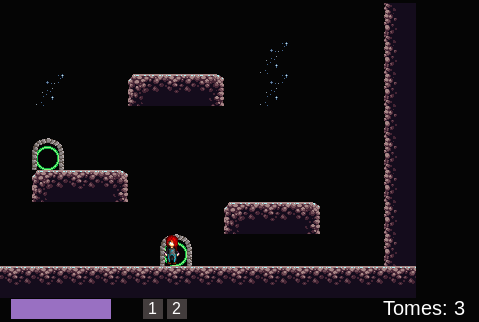

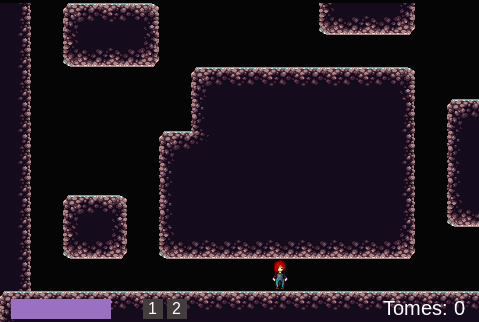

I spent the entire rest of the day just implementing all this logic. Along the way, I decided, instead of a single Objective, to create multiple Objective pickups (which I ultimately decided to call Tomes, giving them a bookish sprite), spawning one on each map, and that the player had to collect all of them to get the “best” ending; anything less would result in achieving a subpar ending. I also wound up having to write a custom events handler to run dispatches at the end of the current rendering cycle as part of making these portals work, as well as a WorldMap handler specifically to handle the metadata outside of each individual map.

Working feverishly, hour after hour, I finally had everything functioning as intended, except for enemy persistence. By now, it was nearly two in the morning. I had intended on composing an original song for this game, but some part of me warned myself that I might not have time for that on the final day, so I listened to a few of my older compositions and picked the best-fitting one as my backup soundtrack.

Lesson Learned: Things will take longer than expected, so account for that when planning.

Utterly exhausted, I collapsed into bed and tried to fall asleep. I tossed and turned, and I growled mentally at my body for being so stubborn…but sleep continued to evade me. At that point, thoughts flooded into my mind about how every minute I spent awake in bed would lead to one less minute of sleep I’d get, because I absolutely could not afford to sleep in late this time, like I did the other days.

After hours of this dreadful torture, I did finally fall asleep, but not for very long.

At 8:00 a.m., the alarm blared and yanked me out of my fitful slumber. Compared to the other days, my mind was besot with grog and lack of clarity from the get-go. I plodded to the fridge, grabbed an energy drink, and started downing it. I had no time to think, no time to reflect; I had to finish enemy persistence, and whatever other little things I’d forgotten, to at least get the game to a playable state.

I thrust myself into the chair before my laptop and got to work. In another couple of hours, I got the enemies to correctly persist across maps. I also implemented a maximum enemy amount per map, and a rate which enemies would spawn/respawn into the map. I also threw in some simple ending screens to test the end-game conditions.

It was past noon by the time I got all this working. Meanwhile, my wife was playtesting builds of the game on another machine, and I would need to run back out there multiple times and pull down the latest builds for her to test with.

At this point, with the core loop finally in place, I decided to start looking around for final art assets. The ones I’d been testing with weren’t bad, but they didn’t quite fit together, and it bugged me enough that I chose to divert time into searching for new assets. Hours passed, and before I knew it the time was 4:00 p.m., and all I had to show for it was a single tileset and new sprites for the character.

The deadline was at 8:00 p.m. In short, I now had four hours to create the actual levels, create music, create sound effects, add story text and cinematics, upload the game to a server, test everything…that’s when it finally hit me: I’m not going to be able to release my full envisioning of the game.

It was at this point that my bipolar symptoms, hitherto under control, started to flare up strongly. Dark thoughts filled my mind about how badly I’d executed this game, how unlikely it was that I would even be able to get it finished. Every tiny little mistake I’d made, from the botched slopes to the overly-long search for a new tileset, flooded into my mind.

“You’re not good enough for this,” my brain whispered to me. “You did your best, but it wasn’t good enough and you’re going to fail.”

I kept trying to push forward with making levels. Nearly an hour later, I only had a single map that looked somewhat decent, and my mental anguish only intensified with each passing minute. There were now entire minutes where I’d find myself paralyzed with derision, my mind crushed under the anguishing weight of despair, my body unwilling to even move a single muscle. It had been a long, long time since I’d felt such intense levels of depression, and this scared me most of all. If this is what it’s going to be like every time, how can I justify making games in the future?

Sanity Wars, indeed. The imagined narrative of my game — of which I had yet to even write a single line of text — proved utterly ironic as the villain of my game threatened to consume the game’s creator.

Somehow, despite mostly working in fits and spurts, I kept forcing myself onward, even as my depression screamed at me about the futility of such gestures. My wife helped out by creating a map of her own, and I threw together a few additional barebones maps with a few randomly-drawn platforms. I found a few open-source sound effects to combine with my sfxr-generated effects I’d already put into the game, and I also took the backup music I’d selected the night before and added it as the game’s soundtrack.

Somehow, with less than two hours until the deadline, I wound up with a playable game. It was nowhere near the game I’d envisioned it to be when I started the competition; compared to that, it was abhorrent, abominable, awful garbage. Yet…it was still a game, and it was playable.

The Dread Overlord was still doing his best to crush my mentality and inconvenience my efforts, but, nevertheless, I slogged on. At this point, I had steeled my resolve. It was going to be a crap game, it wasn’t going to capture the theme nearly as well as I’d planned, and it was surely not going to do well…but I was going to finish and release it, flaws be damned!

Now that I had something to release, it was time to ensure that the game did get released. Although it felt a little early–I still had an hour and a half of time–I decided to go ahead and set up the release platform for my game, so I wouldn’t be scrambling to do it at the literal final hour. As this was a web-based game, my plan was to host this as an AWS S3 website, where I wouldn’t have to deal with setting up and hosting a server, or learning some other company’s setup for their own hosting service. My decision to tackle this now would prove fortunate.

I mentioned previously that I’d built my game-engine based on a tutorial book. Said tutorial book gave instructions on how to set up a dev server called Budo for use with the testing environment…but, it turned out, had not provided any instruction on how to actually deploy the finished app to production. Scrambling, I rapid-researched how Budo ran under the hood, discovered it was using Browserify, and figured out how to set up Browserify to deploy a production build of my game script. After a few other snafus, I managed to correctly set up a deployment script.

Now it was time to create the S3 bucket-site and copy my production assets into it. In my depression-paralyzed state, I screwed up my first deployment attempt and spent almost half an hour trying to fix my AWS permissions before finally opting to blast the first site and make a new one. The second time through, I set the configuration correctly, and the deployment worked as intended. With less than an hour to go before the deadline, I at least knew I could reliably deploy the game.

I used every minute of that last hour to add as much polish as I dared get away with. By now, the adrenaline of deadline crunch was overcoming the dread weight of my depression, so I was singularly focused on trying to make my game at least not absolutely terrible. I converted my test ending screens into actual ending screens, so that I could at least get some of the story’s context into the game. My wife helped by writing the actual dialogue for the ending scenes, while I crafted the introductory scene establishing the game’s tone. We got the final words in, and deployed, at literally the last possible second, at 8:00 p.m.

At the end of the deadline, Ludum Dare allowed for a single hour to get the game deployed, and to fix any last-minute bugs that come up during this process. I honestly don’t recall much of what I did at this time, other than fixing a few things. At the end of it, I belatedly marked the game as “Unfinished” as I crafted the submission post. It only seemed fair, with the game in a barely-publishable state, to mark it as such. When I made my submission post, however, another fellow Ludum Dare-r messaged me, advising me to mark the game as “Jam” instead of “Unfinished”, pointing out that hardly anyone was going to play a marked-unfinished game, and I thus wouldn’t get any feedback on where I could improve. Deciding that I could at least treat this as an improvement opportunity, I took the person’s advice and changed my submission type to “Jam”.

Shortly after I did this, 9:00 p.m. hit. The competition was truly over, and now no changes were allowed. I collapsed onto the living room couch, utterly exhausted and in a foul state of mind. My wife tried to cheer me up, to focus on the fact that I had actually finished and released the game. I wasn’t quite ready to rejoice over that fact, especially since I found myself dreading the horrible reviews which would surely come.

But she was right: I had finished the game. It was a poor excuse of a game, in my mind, but I had actually done it. I’d built a game in three days, and on my first-ever attempt at such a feat. It wasn’t at the standard of quality that I hold myself to, but it was something.

Ultimately, I opted to push all thoughts of self-review and criticism out of my mind until I had gotten a good night’s rest. Fumbling my way through my regular nightly routines, I fell asleep mere minutes after tumbling onto the bed. It was a deep, deep slumber.

I didn’t get out of bed until nearly 10:00 a.m. the next morning. Immediately I noticed an improvement in my mood; sleep had seemed to help tremendously. At the least, I could finally acknowledge to myself that, yes, I had finished a game, and take some pride in that fact.

Lesson Learned: Never underestimate the value of good sleep. Working rested makes a huge difference not only in how you feel, but in the quality of work you output.

Now that the development part of the competition was over, each participant in the jam was expected to play each other’s games, rate them, and provide feedback. I hopped onto my desktop and started checking out the various games. I played a lot of clever implementations of the sacrifice theme: as a game mechanic, as part of a narrative, as the goal for the game…the creativity from the other developers was on full display.

All the while, I kept checking back on my own game. To my surprise, people were not only playing the game…they didn’t completely hate it. Sure, there were critiques on numerous aspects of the game, many of which I was expecting; but there were also plenty of positive comments about some things which they thought I’d done well: the choice of game genre, the incorporation of spellcasting, the visuals and audio… I hadn’t been expecting anything positive, so these comments pleasantly surprised me.

Over the course of the month of December, I continued to play other games (though not as many as I’d have liked, due to work obligations and the holiday season) and give my own ratings and feedback. Other people continued to play my own game and leave their feedback.

At last, at the beginning of January, the ratings period was officially over, and the scores were released for every game. I logged onto the site, and found my results:

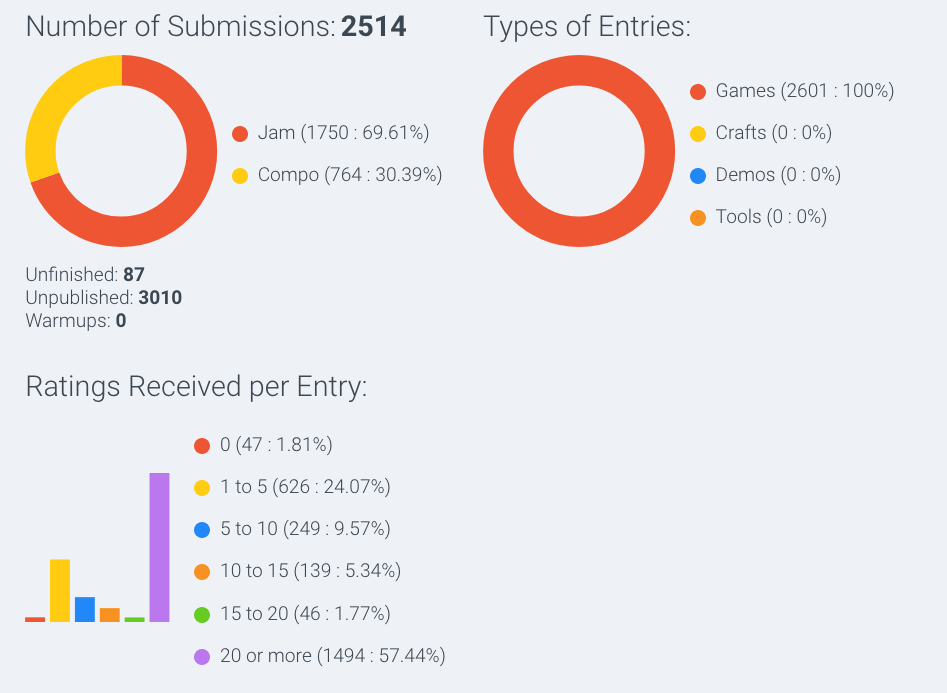

With my own numbers known, I went to check on the overall stats for the jam, from which I’d learn how high my score truly was:

There were 2,514 submissions. Of these, 1,494 had received enough ratings (20 or more) to be awarded an official ranking.

Thus, my final placement: 842nd out of 1,494. Right in the middle of the pack.

To me, the final score was both surprising and expected. Expected, because this was within the middling range where I felt I’d wind up with my first-ever game entry. Surprised, because I never expected this flawed, imperfect game to score so highly. It still amazes me even now, as I type this retrospective.

It just goes to show: Never give up, even when all hope seems lost. This adage is a mantra that I try to live by, contending with my bipolar disorder, and time and time again I find it to be a true maxim. With my emotions screaming failure, I persevered and found triumph.

It’s official, now. Having designed, built, and released a video game, one which people were able to play, I am now a video game developer. It feels good to say that, after all the learning and preparation I put in to get to this point.

Overall, this competition was an incredible experience for me, in many ways. I set out to make my first-ever game, and I not only succeeded, I did better than I expected of my entry. Though I still wish I had been able to release a more polished game, the experience I’ve gained was invaluable, and will prove critical to my future endeavors to publish a full-fledged video game.

Among the things I learned: coding a game engine from scratch is hard. I mean, I knew that, and I knew that the main reason I did build an engine was to learn how things worked from a general perspective, but it gave me a whole new appreciation for the work game engine developers put in to make usable, reliable engines for others to use. Although I like tinkering with systems and how things work under the hood, Sanity Wars drove home a well-worn adage in the games industry: make games, not engines.

I also think I tried too hard to come up with a complex narrative for a game that, ultimately, did not need much narrative involvement. Presenting an allegory of the bipolar struggle may be neat for short stories, but it didn’t translate well into a game. I’m a narrative-oriented person, so I like creating complex narratives; however, by focusing too hard on cleverly implementing sacrifice in Sanity Wars‘ narrative, I instead sacrificed the fun of the game mechanics. In the end, I felt neither the narrative nor the spell sacrifice was well-implemented, and I could have done both more simply by highlighting the sacrificial nature of tying spellcasting to your health.

My goal with taking part in Ludum Dare was to gain experience, and in that regard I achieved success. Most of all, I learned that I can, indeed, create video games, and that this is something I want to keep doing, depression be damned

To put it in a melodramatic way…I faced the Dread Overlord, and conquered him

I am currently working on rebuilding Sanity Wars in Godot, an open-source game engine, and comparing the experience to coding everything by hand. I suspect it might ease many of the pain points I had developing my game and engine.

Why did I choose Godot, over something more familiar to my background, such as PhaserJS? Well, I read plenty of good things about its ease of use, and the node-based architecture is very similar to the structure I used in my own engine. Plus, I thought it’d be nice to have a GUI to work with, instead of coding everything by hand. I plan on releasing the Godot version of Sanity Wars once I’ve finished the port.

The next Ludum Dare is at the end of April. I’ve already made sure to take time off for the dates of that contest. I look forward to taking on whatever challenges it throws my way, with the goal of releasing a more polished game.

As for my dream of making a professional video game? That dream is alive and well, and as I continue to learn and grow my skills, my confidence that this dream can be realized continues to grow. And as long as I keep moving forward, and don’t give up, I have no doubt that one day this will no longer be a dream.

It will be reality.

This is part two of a multi-part series about React and Vue.

Part 1: React

Part 2: Vue

As I have been learning React lately, I’ve also been learning Vue. I currently use Vue at work, but I wanted to make a sample project for myself. I’ve been interested in doing a comparison between React and Vue, so I’ve chosen to build a Vue version of the Star-Rating app I built in React. The app is small and simple: you have a rating represented as a line of stars, and you can change how the star rating is calculated via an inputs component.

For the final result, click this link.

This tutorial presumes a basic knowledge of HTML, CSS, and JS, along with some basic knowledge of how to develop using a command line interface (or CLI) and how to use Node Package Manager (or NPM). If you’re unfamiliar with any of these things, feel free to make an online search for whatever you don’t know.

Vue makes some use of ES6 syntax, and I try to write my code using ES6 as well. I’ll try to link to definitions of ES6 syntax when I initially use them, but I won’t take especial time to explain them in-depth. If you want a quick overview of ES6, you can read this.

Setting Up

Looking Around

Creating Our First Component

Rendering Stars with FontAwesome

Calculating How Many Stars to Render

Rendering the Stars

Vue Slots

Finishing the First Component

Introducing a Second Component

Rendering the Input

Adding the Other Inputs

Better Validation

Final Touches

Conclusion

For this tutorial, I chose to use vue-cli, a command-line tool that will set up a boilerplate Vue single-page application, similar to create-react-app. If you don’t have it already, you can install it via npm install -g vue-cli@2.9.3.

I’ve specified a specific version number because, as of this post, vue-cli V3 is in beta and will be released soon. It works differently from V2, so to follow this tutorial you’ll need a V2 version of the tool.

To set up a project, navigate in the terminal to the directory you want to make the project in (for me, this is ~/jdev/projects), and then enter this command:

vue init webpack star-rating-vue

Right away, you’ll be presented with a text interface that asks you a number of questions regarding how you want to set up your project. But, before we get to that, let’s look at the command we just entered. The first part is vue, calling the tool; the second part is init, which tells the tool to start up the project; and the fourth part, star-rating-vue, is the directory our app is going to be saved in. So what is the third part, webpack, for? The way vue-cli V2 works is by using pre-built templates, and which template you choose determines what kinds of goodies you start out with. In this case, we’re using the “webpack” template, which will set up a full Webpack-based project, as well as a few other things:

If you look on the official page for vue-cli, you’ll find some other “official” templates you could use, instead. There are also third-party templates; just search online for “vue third-party templates” and you’ll be bound to find some.

Now that we’ve taken a brief overview of what templates are, let’s get back to the actual setup. The command line tool will present you with a set of options, one at a time. For most of the options, you’ll need to type in either y or n and hit enter to make your choice; some are multiple choice, and a few involve typing up strings.

I’ll go over each option briefly:

Runtime + Compiler and Runtime-only.

Runtime + Compiler allows more flexibility in how you build your projects, such as passing in templates as a string (from an AJAX call, for example), but it makes the final build larger (by as much as 30%).Runtime-only is a lighter build, and performs slightly faster, but imposes some restrictions on how you can set up your project.We shouldn’t need any functionality from the compiler for this project, so let’s select Runtime-only.

vue-router is useful for setting up something resembling url navigation within an SPA. We won’t be doing that here, so you can choose n.y, and then pick the linter you want to use in the subsequent section. Otherwise, choose n.n.n.Yes, use NPM. If you prefer Yarn, you can choose that instead.After that last choice, vue-cli will get to work setting up your app with the choices you’ve made. It may take a while, depending on your internet speed, but in a minute or two your boilerplate app should be generated and ready for you to work with. When it’s finished, start the development server by cd-ing into the project directory and typing npm run dev. Open a browser and navigate to localhost:8080; if you see the Vue logo and some links, the dev server is successfully running!

If you don’t want to use vue-cli, you can import Vue directly, via a CDN, locally-hosted script, or NPM install. Check out the official docs for more information. For this tutorial, however, I’ll be assuming you’re using vue-cli.

Now that we’ve (finally) got the barebones project set up, open the project in your preferred code editor.

If you use VS Code, you can spawn a new editor window from the project directory by cd-ing into it, then typing

code .(you may need to explicitly enable this if you use a Mac). Other code editors likely support this functionality as well, though the commands you use may be different.

You should see a number of directories and files already set up. Let’s look in the src directory and open up the file called main.js. It should look something like this:

This file sets up the root Vue instance. All the other components in our application will be kept under this root instance. We’re importing Vue itself, as well as a file called App (which we will be examining shortly). There’s a quick line disabling the production tip. Finally, we create a new Vue instance, and pass in a config object with two settings:

el: '#app' This tells Vue what element from the HTML document to bind the instance to. The original element will be replaced with our rendered application. (You can see this element by looking in the `index.html` file in the project root directory.)render: h => h(App) This tells the instance’s render function what should be rendered, via passing in a callback function that handles the actual rendering. In this case, we’re rendering the App file imported at the top of the page.Let’s dig into that second option a little bit. The code is using an ES6 arrow function, with a single argument: h. What’s h? It’s an alias for the createElement function, the letter itself short for “hyperscript” (you can check this Github issue comment for a deeper explanation of both the render prop and the meaning of h). h is then called, and App is passed in and rendered.

So what is App doing? Let’s find out:

Note the .vue extension. This is what Vue calls a Single File Component. A single file component allows you to write your HTML, JavaScript, and CSS for that component in the same file. For applications comprised of multiple, modular parts, this can be very useful for keeping markup, logic, and styles associated with a single component located in one place. We will be creating our own single file components (henceforth just “components”) soon enough, but first let’s dig into the default App component, section by section.

First, the HTML:

The entire section is wrapped in a template tag. This gives Vue access to the markup contained within; the tag itself will not be rendered. Next, you have a single div with an id of app. This is not the same app element that the root Vue instance replaced; it merely shares the same id. Finally, we have an image tag — the Vue logo — and a strange-looking, self-closing tag named HelloWorld. This is another component, imported into App and being rendered below the logo.

All elements in your component must be wrapped by a single container element; here, the

#appdiv.

Next, in the javascript section:

This contains the JavaScript code for the component. First, you’ll see the HelloWorld component being imported from the components directory. Next, the code exports an object as default, containing two properties:

<HelloWorld/> in our template and have Vue replace it with the template from the HelloWorld component.Finally, there’s the styles section:

This is just regular ol’ CSS, styling the #app element. During development, these styles will be added to the <head>, but because our Webpack template includes CSS extraction, the styles in this section will get pulled out and added to a single CSS file during the build stage.

That does it for App. Now let’s look at the other component included in the boilerplate — the HelloWorld component.

As you may have noticed, the attributes for the

atags in your local file are split onto separate lines. This is considered by Vue’s style guide to be best practice. I’ve chosen to condense the tags back onto one line for my gist for the sake of brevity, but in general I agree with this philosophy.

It’s another single file component. The HTML template contains a couple unordered lists of links and some h2 tags titling them, as well as an h1 with {{ msg }}. If you’re looking at the app in the browser, however, the h1 says “Welcome to Your Vue.js App”. What’s going on?

Let’s look in the script section to find out:

There isn’t much here. We have the component’s name, “HelloWorld”. There are no components being passed in; however, we do have a method called data, which returns an object. This object contains one property: msg, whose value is set to “Welcome to Your Vue.js App”. Hey, that’s what the h1 says on the rendered page! That’s where it comes from. Anything you set in a Vue component’s data method becomes available in your template as a variable. You can output the values of those variables using a pair of curly braces.

Why is data a method returning an object, instead of just being a property set as an object? If you have multiple instances of the same component on a page, each component’s properties are shared with each other by reference. Thus, if data were an object, updating the data on one component would update that piece of data for every instance of that component. To avoid this, we just make data a method that returns a fresh object each time it is called.

The docs provide additional explanation, as well as an example.

Lastly, let’s take a look at the style section for this component:

Again, it’s just CSS, but this time there’s a scoped attribute in the style tag. This means the CSS in this component will only be applied to styles within that component. How does it do this? If you go to the web page and do a dev inspection on one of the links, you’ll notice there’s a data attribute attached with a long, random string (prefixed with data-v-) as its value. Vue sets the CSS rules in HelloWorld to target both the rule specified in the code and the value of this data attribute. Thus, the styles in this component will not affect anything outside of its scope.

You are still able to affect the element styles in this component from the outside, but be aware that, since the data attribute specification adds specificity, you may need to be more explicit with your rule declarations than usual to override the component’s styles.

Whew! For a boilerplate example, that was a lot of stuff to look over. Hopefully, this overview gave you a basic idea of how Vue works; the rest of what we need to know, we’ll pick up as we go along. Let’s start making our Star-Rating app by creating our first component!

In the “components” directory, create a new file and name it StarRating.vue. Here’s the structure we’ll need to start with:

In the template section, we’ve just added a single div with a class of “star-rating”, which will serve as the container element Vue requires. That’s all we’ll add, for the moment; we’ll get to adding stars shortly.

In the script section, we’re exporting a default object with two properties: name, and props. Props are pieces of data that a component expects to be passed down from a parent component. We’ll be setting up App to do that, but for now we’ll just set up defaults to work with. We’ll also add a type property to each prop, which allows Vue to detect when a prop gets passed down that doesn’t match the type specified, and warn you in the developer console.

The style section is currently empty. Eventually, we’ll put in the styles specific to the StarRating component, but first let’s have something to actually render.

If you read the React version of this sample project, you’ll remember that we chose an icon set called FontAwesome, imported some star icons into our app via a series of NPM libraries, and wrote some logic to control how to render those icons. We’re going to do the same thing here, but instead of using react-fontawesome, we’ll be using vue-fontawesome.

npm i --save npm i --save @fortawesome/fontawesome-svg-core @fortawesome/fontawesome-free-solid @fortawesome/fontawesome-free-regular @fortawesome/vue-fontawesome

To summarize, we’re installing Fontawesome, two sets of Fontawesome icons, and a package which provides FontAwesome Vue components. Once the packages have finished installing, we need to import them into our project.

First, in App.vue, replace the HelloWorld import with this:

The first statement is importing the main fontawesome library. The next two import statements are using multiple import syntax to extract specific parts of the fontawesome-free-solid and fontawesome-free-regular icon libraries. For the latter, we are also assigning aliases to the imports, since they share names with the solid counterparts. Finally, we use fontawesome.library.add() to make these four icons globally available for all our other components to use.

We could also have just imported all of a library’s icons — with, say,

import solid from '@fortawesome/fontawesome-free-solid'— and added all the icons globally. If you know you only need a small set of icons, however, it’s best to just import the ones you need.

Next, let’s go back to StarRating and add one more import:

Similarly to how we imported parts of the icon libraries, we are importing parts of the @fortawesome/vue-fontawesome library — specifically, FontAwesomeIcon and FontAwesomeLayers. Soon, we’ll be using these to render our star ratings. First, though, we need to tell our StarRating component to make these FontAwesome components available to the template, and that’s what we’re doing by adding the components property to our exported object, its members FontAwesomeIcon and FontAwesomeLayers.

With our FontAwesomeIcon component imported, let’s go ahead and update our template:

Inside the container div, we’ve added a new tag: font-awesome-icon. This is our FontAwesomeIcon component, and when Vue renders our app it will take this component tag and replace it with the component’s template, just as the HelloWorld component is being rendered into our default application. We’ve given it a class of “star”, and we’ve also set a property named icon, its value set to “star” as well. This icon property is a prop we are passing down to the Vue component, telling it which icon we’d like it to render.

The official Vue style guide strongly recommends naming custom components using multiple words, as well as naming your components using either all Pascal-case (FirstLetterCapitalized) or kebab-case (dashes-between-words), and I agree with their reasons. For our tutorial, I’ve chosen to use kebab-case, but ultimately it’s just a matter of preference.

Let’s go ahead and render our new component into the App.vue component file:

We’ve added an import for our StarRating component before the other imports (imports are asynchronous, so JavaScript will not execute any code until all imports have been processed, which means we don’t have to import StarRating after our FontAwesome imports). We’ve also removed the import for HelloWorld because we won’t be needing it. In components, we replace HelloWorld with StarRating. Finally, in template, we again swap HelloWorld for star-rating. If all goes well, upon save you should see a single black star rendered just below the Vue logo.

If you played around with the final result at the beginning of the tutorial, you may have noticed three different types of stars: “full” stars, “half” stars, and “empty” stars. This is how I’ve chosen to represent the star ratings for this project.

Before we can render any of that, though, we need to calculate four things:

You may be wondering why it’s necessary to calculate a “maxStars” value. Sure, we could simply calculate the full, half, and empty star values without calculating a separate max value, but I’ve found that it makes the math simpler to just figure out the maximum number ahead of time and use it in calculations later, so that is what I’ve chosen to do.

Let’s update the StarRating component with the necessary code to perform our calculations:

To briefly explain each calculation:

Note where we have placed these methods. These are what Vue calls “computed properties”. In other words, when you access these properties, whether in your template or other parts of your code, Vue will return the result of the function you’ve assigned to that computed property.

If you examine the code used for the emptyStars method, you can see that we’re using the other three computed properties to calculate its return value. The other three computed properties, in turn, are calculated based on the value of the props passed in to the StarRating component. If any of the props should change, Vue will recalculate the values of these computed properties, and any rendered data using these computed properties will also be updated; it all happens automatically.

Let’s see the computed properties in action. Modify the template thusly:

What we’ve done is add a directive to our font-awesome-icon component called v-for. This directive is telling Vue to render a component this many times, just like looping through a list of items. The text inside of the v-for directive is actually specific syntax that Vue will interpret similarly to a for-in loop. Vue lets you enumerate objects and arrays with this syntax, as well as ranges (which is what we’re using in this case).

Be sure to check out Vue’s official documentation on this subject, which shows you more specifically how to work with arrays and objects using

v-for.

We’ve also added a key attribute, and you might have noticed the colon in front of it. What is this colon for? This is a shortcut for the directive v-bind, which binds an HTML attribute to a JavaScript expression. The value of key equals "`fs${fs}`", which is a template literal expression. To use ES5, "fs" + fs (which would also work here; I just prefer using ES6 when possible). When Vue reads this, it will parse the expression bound to :key as actual JavaScript.

You can read more about attributes here. If you follow the link, you’ll notice that the Vue examples use

v-bind:instead of just the colon. That is the “full” way to write out binding syntax, but Vue allows you to use just the colon as a shortcut.

Why do we need key? Vue strongly recommends that you add a unique key to each item rendered by a v-for loop because it helps Vue track each item in its virtual DOM, which ultimately improves performance. The expression set in key will generate a string with the incrementing value of the variable fs (set in the value of v-for), which is enough to make this key unique. Since, technically, it isn’t required, we could choose to leave the key out, but it’s good practice to always add a key attribute when using v-for.

So what does all this actually do? If you’ve saved this code, you might have already noticed that the demo app in the browser has already updated to show two black stars instead of one. This is because of our v-for directive, fs in fullStars. The default prop value for rating is 5, and our default starRatio is 2. Those two props are used by the fullStars computed property to calculate its value, and in this case the result is 2. v-for then loops n in 2, resulting in rendering the font-awesome-icon component twice. Again, this happens automatically. You don’t have to write a separate function to handle the looping and rendering for you. Vue just takes care of it because you told it to via the v-for directive.

Now that we know how this works, let’s go ahead and add the template code to render our half stars and our empty stars:

The process for rendering our half stars and empty stars is nearly identical to the process for rendering full stars. We just add a FontAwesome component and use v-for to render as many of each component as dictated by the related computed properties. There are a few differences, however, which I’ll go over briefly.

In both cases, we need to generate unique keys for the key attribute, and to accomplish this we just change the variable to match what we use in the v-for directive and alter the string prefix. For the empty stars, "`es${es}`", and for half stars, "`hs${hs}`".

For the empty stars icon component, instead of just passing in an icon attribute, we’re binding the attribute to a JavaScript array: ['far', 'star']. This is because of the font-awesome-icon component’s interface. By default, passing in a simple icon attribute will render an icon from the solid library of icons, which is what we used to render our full stars. For empty stars, however, we want to render a different icon; specifically, one from the regular library that looks like the empty outline of a star. In order to tell the font-awesome-icon component to render an icon from the regular library, FontAwesomeVue expects us to pass in an array with two members. The first item is the abbreviation of the library we want to pull the icon from, in this case far; the second item is the name of the icon we want, in this case star. Since we’re passing in an actual array, that means we need to bind icon so we can send the configuration array to the component.

You could use

['fas', 'star']to render our full star icons, instead of relying on the component’s default assumption, if you prefer.

The most significant difference is with how we’re rendering the half stars. Instead of a single font-awesome-icon, we’re rendering two, and we’ve wrapped both components with a font-awesome-layers component. This is because FontAwesome 5 (the version this tutorial is using) doesn’t have a “half-filled” star icon; instead, it has a literal half of a star: one that is “filled” (from solid), and one that is “empty” (from regular).

To get the half-filled star effect we’re looking for, we need to combine those two icons into one. The official way to do this in FontAwesome is to use Layering; in vue-fontawesome, this means using the font-awesome-layers component. Anything within the font-awesome-layers tags will get combined into the same space and be shown as though it were one icon.

Thus, we’ve set the two font-awesome-icon components to use the half-star icons; additionally, we pass in a flip attribute to the empty half-star so it’s reversed. The end result is something that looks like a half-filled star. Excellent!

After I started writing this tutorial, FontAwesome did come out with a half-filled star icon, so we could use that instead of my original solution. I’m not going to change this solution, however, because it also serves to teach about Vue slots — which is coming right up!

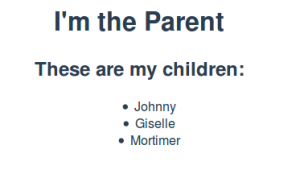

Let’s take a moment to further examine font-awesome-layers. Up until now, we’ve been using self-closing tags for our components, because it’s simpler to read and we had no need to use opening/closing tag syntax. With font-awesome-layers, however, we’re not only using opening and closing tags, we’re including other components inside of the tags. This is using an aspect of Vue components called slots. To explain what slots do, let’s use a quick example:

The above code (assuming path names and whatnot) results in rendering the following:

In the first component, called ExampleComponent, we basically have two parts: an h2 with the text “These are my children:”, and a ul containing a slot tag. What is this slot tag for? This is telling Vue that anything which is slotted into this component should go here. What does slotting mean, though? To answer that, let’s look at the second component.

The second component is called ExampleParent. In it, we have an h1 with the text “I’m the Parent”. What comes next is our first component, example-component, but in between the opening and closing tags of example-component are three li tags, each containing a human name. If you look at the results image, you’ll see that it renders “I’m the Parent” (from ExampleParent), followed by “These are my children” (from ExampleComponent), and lastly by the names (from ExampleParent). Vue is taking the li tags we enclosed within the example-component tags and inserting them in place of the slot tag we put in ExampleComponent. That is slotting.

If you’d like to follow along, you can copy-paste the code snippets into your

componentsdirectory as separate Vue files, and then importExampleParentintoApp, just like we did withStarRating. Don’t forget to remove it when you’re done with it!

Now that we have a better idea of what slots are, let’s look at the font-awesome-layers component again:

We are slotting two font-awesome-vue icons inside of the font-awesome-layers component. That layers component will then render FontAwesome’s layers container (basically a div container and some classes), so we can make those two half-star pieces look like a half-filled star.

Alright, we’ve added the code necessary to render all of our stars: full, half, and empty. The last thing we’ll do (for now) is add some styling in the style tags at the bottom of the StarRating component. The finished* code should look like this:

Following the steps outlined so far, you should now see the Vue logo with two and a half gold stars rendered beneath it. If you do, congratulations on making it this far! If not, you should review your code and compare it with what I’ve posted. Hopefully that should expose your problem and get you back on the right track. If not, feel free to submit an issue in the project repository!

Did you notice the asterisk on “finished”? There’s one more thing we’re going to take care of later, but we don’t need to worry about it right now.

Assuming things are working, let’s go ahead and pass a prop down to our component. From App.vue:

When you save the file, you should see the rendered stars change. Assuming you passed in a “7”, like I did, there should be three and a half stars rendered — three full, one half, and one empty. Vue took the rating number we passed down to the StarRating component and converted it to the star rating we now see. We didn’t have to do anything other than pass down that prop.

Of course, at the moment we can only change the rating by manually editing our code to change the value of the rating prop. That obviously isn’t a very user-friendly way to change the star rating, so we’re going to want to have an interface for us to enter the prop values we want and have StarRating update in response, as shown in the final result. To do that, we need to build a second component specifically for handling this interface…a RatingInputs component!

To begin, let’s create a new file in the components directory, and call it RatingInputs.vue. Add the following code:

First, in the template, we have a single input for the rating, as well as a label for that input, all wrapped in a container div. Then, in the script section, we have the component’s name and our prop definitions (like we had in the StarRating component). Finally, we have the empty style tags at the bottom.

Next, we’ll take advantage of Vue’s form input bindings and wire up our input element to the component’s data:

We’ve added a directive to the input, v-model, and set it equal to rating_. In the script section, we’ve added a data function, which returns an object containing one property: rating_ = this.rating. What this is doing is initializing rating_ with the value of rating, a prop this component expects to be passed down (and if it isn’t, then it defaults to 5, as we set up in the props section). Because we’ve told Vue to “model” the value of rating_ on our rating input, Vue sets the input element’s value equal to the value of rating_; when we change the value in the input element, Vue then updates rating_ to equal the new value. Thus, Vue gives us two-way data binding without having to do extra work.

Why not just set the input’s value to be rating directly? Technically, Vue would allow us to do that; however, this is considered bad practice. The reason is because anything defined as a prop will have its value changed any time a new value is passed down to the prop via the parent component. Thus, as best practice, if we want to modify a prop’s value from the child component, we should instead create a property in the data object and initialize it with the prop’s value, then modify that data property instead of the prop.

There is no established nomenclature for how you should name your props and data values in cases like these. I’ve chosen to use

ratingas the prop name for easier reading when passing it in from the parent, andrating_because Vue doesn’t allow you to start data fields with underscores, and this seemed the next best thing.

Although our RatingInputs component is wired up with the rating input, we still don’t have a way to tell the StarRating component what that input’s value is. To do that, we’re going to need to use Vue’s events system. We’ll start by updating our RatingInputs component:

We’ve added another new directive to the input element: v-on. This tells Vue to listen for an event (it can be a browser or custom event) emitted by this element. :input tells Vue which event to listen for, and "handleRating" is the callback we want Vue to run on this event. In the script section, we’ve added a new property to the component object, called methods. This is where you store any functions you want your component to have access to.

You should use regular functions here instead of arrow functions. Vue automatically handles binding a component’s

thisto its methods, but it can’t do so for arrow functions because those use thethisvalue of the calling function — which, in this case, won’t be theRatingInputscomponent, but Vue’s handler for methods.

In methods, we’ve added one function: handleRating, which does two things: first, it gets the value for rating_ from the component via destructuring assignment; second, we call this.$emit, which is a special component function to emit a custom event that only a direct parent component will be able to read. This $emit function takes, as its arguments, a string “rating-update” and an object literal set to {rating: rating_}. rating-update is the name of our custom event, and the object literal is an argument that will be passed in to any callbacks the parent App component has listening for the rating-update event.

Now, in App, let’s make some changes to listen for our custom event:

In the template section, we’ve removed the hard-corded value for :rating and changed it to be the value of the rating data field, which we add in the script section. We’ve also added the rating prop to our RatingInputs component, as well as @rating-update, the custom event that we’re listening for, and a handleRatingUpdate callback.

@is Vue shorthand syntax forv-on:

We’ve added a methods object to the App component object, as well as the function handleRatingUpdate. It takes one argument, data, which is equal to the object literal we passed into the $emit function in the RatingInputs component. From data, we extract the rating property, and then set this.rating (the data field in App) to equal rating. Upon saving the file, we should now be able to edit the value of rating input element and update the rendered stars in real-time. If you’re able to do so, congratulations!

While playing with the ratings input, you’ll likely notice that you can add a higher input than 10, and a lower input than 0. While this doesn’t seem to affect anything visually, this is not ideal behavior. We want to limit the input so that the user can’t add a higher rating than the maximum, or a lower rating than the minimum. Also, it would be nice to be able to change the star ratio, or how many stars get rendered per rating point (e.g. render one star per rating point, rather than one-half). Let’s get on that.

Let’s start by adding additional inputs for the values outlined above: maxRating, minRating, and starRatio. The code for both RatingInputs and App is as follows:

As you can see, the majority of we needed to do is replicate the code we added to wire up rating, changing only the names. We use the same handleRating callback to process any change to the inputs and pass them up to the parent, and likewise handleRatingUpdate updates all the data fields at once. We then pass back the data in App as props to both StarRating and RatingInputs, and each component updates its own data accordingly.

There are a couple of additional changes. First, all of the input elements have min and max attributes set, which will show an error highlight should any of the values go below the minimum or above the maximum. There’s also a limit property, which is used to constrain minRating and maxRating; this is mainly to control how many stars can actually be rendered, as rendering more than a thousand begins to negatively impact performance.

We still haven’t solved the problem of preventing someone from inputing illegal values into our data. There are a variety of conditions we’ll need to check, and we’re going to need to check them for both StarRating and RatingInputs. It seems like it would be a good idea to write a separate file that contains all this validation code, which we can import into whatever files need to use it.

Conveniently, I’ve already written such a library for the React version of this project. Since we’re validating the exact same set of data, we can just take that file as-is and plop it straight into our Vue project.

In your src directory, create a new directory and name it lib, then create a file called validate.js and copy-paste the following code into it:

The function we’re most interested in is the default export, which is a function that runs all the other validation functions in the file, returning false if any one of the checks fail, and only returning true if all the checks pass. All we have to do is pass in our data values.

We have the validation library, but now we need to integrate it with our app. Let’s start with the RatingInputs component.

The only place where we needed to make changes was the script file. First, we import the library. Then, in the methods section of the component, we’ve added a new method: anyAreEmpty. All this does is check any arguments passed into it and return true if any of them are equal to an empty string. In our handleRating method, we then use anyAreEmpty to check each of our input values to make sure they aren’t empty strings. Why did we do this? A more detailed explanation can be found in this section of the React tutorial, but the gist is that without doing this, there are scenarios where Vue (and React) won’t let you update the inputs at all.

Finally, we’ve wrapped our call to $emit inside of our validation function, inputIsValid, which takes all of our data values as an argument. We’ve also moved our number conversion to occur before we run the validation function; otherwise, we’d be passing strings into the validation functions, which are expecting numeric values. Only when the validation function returns true do we emit the rating-update event.

With RatingInputs taken care of, let’s turn to StarRating and make a small change there (this is what the asterisk from earlier was for).

Here, we’ve added a new property to the component, called beforeMount. This is one of Vue’s lifecycle hooks, which are basically functions Vue calls at specific stages of a component’s life. In this case, beforeMount will be called once, right before the component is rendered for the first time. We’re checking to see if our default props, being passed in from App, are valid, and if they aren’t we throw an error to let the developer know that they need to check the values being passed as props.

You might be wondering: Why bother with this validation at all? After all, this validation check isn’t what’s showing the errors to the user; the browser is handling that. All this is doing is preventing the rating-update event from being emitted when an illegal value is entered. But that’s the point: without this validation, Vue would emit the event, try to process the illegal values, and then error out in the process. We’d be wasting processing effort doing something we already know is not going to be valid. While that’s not as significant an issue for a small demo app such as this, there are plenty of cases where this would be a costly error. For example, say our update event triggered an AJAX request; we wouldn’t want to send an HTTP request whenever an illegal value is entered. By making sure we only update when our input values are legal, we ensure our code isn’t wasting resources and processing power.

While I’m not going to do this here, we could also use our validation library to trigger more specific error messages in response to the illegal inputs. Feel free to add this yourself, if you’d like!

With this, all that’s really left to do for RatingInputs is add some styling. If you want to fully match the way my version of the app looks, add the following style section to RatingInputs:

We should also change the styling on App so that the visual structure looks better (up until now we’ve been using the default styles that were generated by Vue when we created the app). I also made slight changes to the App template. To match my version of the app, add the following style section to App and modify the App template to match mine:

Of course, if you want to style things differently, feel free to do so!

Hopefully this was a fun app to build. I liked making a demo app that wasn’t a todo list. Vue felt intuitive to me, as a web developer, and I loved being able to use template files to keep everything relating to a single component in one file. In exchange, you do have to structure your app in a more specific way, but since I mostly agree with how Vue wants you to do things, I don’t consider this a bad thing.

If you want to view the entirety of my code, look up the project on my Github repo.

Questions? Feedback? Leave a comment!

This is part one of a multi-part series about React and Vue.

Part 1: React

Part 2: Vue

Lately, I’ve been learning React, a JavaScript front-end framework. As of now, it is one of the most popular JS frameworks in existence. To help myself learn the framework, I built a sample project: a Star-Rating app. It functions similarly to what you might see on Amazon, where you have a rating represented as a line of stars. You can change the parameters used to calculate the star rating via an inputs component.

To see the final result, click this link.

I think it turned out rather nicely, and today I’d like to show how I built it, and in the process explain how React does things, as best as I currently understand it.

This tutorial presumes a basic knowledge of HTML, CSS, and JS, along with some basic knowledge of how to develop using a command line interface (or CLI) and how to use Node Package Manager (or NPM). If you’re unfamiliar with any of these things, feel free to make an online search for whatever you don’t know.

Setting Up

Looking Around

Creating Our First Component

Rendering Stars with FontAwesome

Calculating How Many Stars to Render

Rendering the Stars

Adding Our New Component

Introducing a Second Component

State and React

Passing State Between Components

Wiring Everything Else Up

Better Validation

Bug Hunt

Final Touches

Conclusion

To start the process, I chose to use create-react-app to handle creating the base project structure. You can get it through NPM. Using the command line:

# Install create-react-app. You only need to do this if you don't already have it installed.

npm i -g create-react-app

# Create a new React single-page app.

create-react-app react-star-rating

# Navigate to the app directory and fire up the development server.

cd react-star-rating

npm start

After performing the above instructions, a tab should automatically open up in your default browser to localhost:3000, which should be a page containing a spinning React logo and some additional text.

It should be noted that you don’t need to use create-react-app to make a React project; instead, you could just include CDN links of these two scripts in an HTML file:

<script crossorigin src="https://unpkg.com/react@16/umd/react.production.min.js"></script>

<script crossorigin src="https://unpkg.com/react-dom@16/umd/react-dom.production.min.js"></script>

I find create-react-app offers conveniences that are useful, such as hot reloading (changes are updated as you save your files) and a development server (so I don’t have to set one up myself), so I usually prefer to use that. This tutorial will assume that you are also using create-react-app.

Now that we have the barebones project set up, let’s open the project directory in a code editor. You can use whatever editor you wish; I personally use the free editor Visual Studio Code, but there are plenty of other excellent options, such as Atom and (if you’re willing to spend money) Sublime.

Once you have the project open in the code editor, you should see there’s a bunch of files already set up. Let’s look in the src directory and open up the file called App.js. It should look something like this:

One thing you’ll notice right away is the use of import and export statements, as well as the use of classes. These are all part of the ES6 syntax. React makes heavy use of ES6 features; if you’re not familiar with ES6, here is a quick guide of basic features. Not all ES6 features are yet included in modern browsers (as of this writing), so one of the things create-react-app provides is a “transpiler”, which automatically converts ES6 syntax to its ES5 equivalent, so browsers know how to read the code. If you want to work with React, I’d recommend becoming familiar with ES6 features and how to use them; once you know how it works, ES6 lets you do really powerful things.

I’ll occassionally point out instances where I’m writing ES6 and compare it to the ES5 version so you can see how much simpler ES6 can make things look.

So, what is the code for App.js actually doing? Let’s do a brief examination.

These import statements are including external files into our file. We can even use imports to add specific parts of a file to our app, which is what { Component } is doing. Notice that we can import more than just JavaScript; we’re also including a logo image (logo.svg) and our app’s CSS file.

Here, we are using an ES6 feature — classes — to extend the Component class, which means we are getting access to all the functionality that a Component class has. If we were to use ES5 syntax, we wouldn’t be using class syntax at all. Instead, we’d be calling a React function called createClass, like so:

Both this snippet and the one previous do exactly the same thing: create a new React Component class.

So, what is the “render” function for? Primarily, it is responsible for rendering our component’s HTML. You might have noticed the HTML elements being returned by the render function:

Strictly speaking, this isn’t actually “HTML”. It’s something called “JSX”. The React site gives a good explanation of what JSX is, but to summarize, it’s a way to write HTML markup using JavaScript. This is one of React’s biggest features: the idea that components return their own HTML to render on the page. Some people really love the idea, as it allows you to keep the logic and markup of a component in the same file, which can make it easier to reason about an app’s logic. The JSX makes it easier to understand what the component’s markup looks like. React takes care of converting JSX to rendered HTML for you.

Some say that you shouldn’t mix JavaScript and HTML/JSX together. If you belong to this camp, then you don’t have to use JSX at all. Everything you can do in React using JSX, you can also do through pure JavaScript. The following code does exactly the same thing as the previous snippet, but just using JavaScript:

As you can see, under the hood JSX is just a series of JavaScript functions and objects, which end up creating our HTML elements. Personally, I find this syntax more difficult to read, and thus harder to reason with when I’m building an app, so I like to use JSX. That’s what I’ll be using for the remainder of this tutorial.

There’s another point of interest we should look at in the JSX code: the {logo} which is being set as the image tag’s source. In JSX, if you want to use JavaScript variables, you can do so by adding that variable directly to the JSX code, enclosing it in curly brackets. This is what will allow us to show various bits of data that we calculate with JavaScript.

Finally, at the end of the file, we have one final line:

As we use import to pull stuff in from other files, we use export to send stuff to other files that want to import our code. In this case, we are exporting the App component class.

Now that we’ve analyzed the App.js file provided by the boilerplate code created with create-react-app, and in the process familiarized ourselves a little bit with how React works, let’s start actually creating our app!

First, let’s make a folder called “components”, which will house all of our component files. With our components folder created, let’s add a new file to it: StarRating.jsx. Note the .jsx extension. It signifies that we are using JSX in this file. You could, technically, just make it a regular .js file (and, if you noticed, the file we looked at earlier is App.js), but I prefer to use the .jsx extension because it helps me know which components are rendering HTML.

Now that we have our first component’s file, let’s write some code.

This is just adding some code to get us started. We import React and the Component class, and we export a new class, StarRating. I’m defining the class as part of the export, instead of creating the class first and then exporting it, as we saw in App.js. Either way works; I prefer to use this method. We also create a render function and return a single <div>, with a class called star-rating. Note that, instead of class, we use className. Since JavaScript itself uses the word “class”, when writing JSX we need to distinguish between an HTML class and a JavaScript class, and this is done by using className when writing an element’s classes.

You may notice that I’m not using semicolons when writing my JavaScript. In many cases, the browser takes care of adding the semicolons you need, so you don’t actually need to write them yourself. This is just a personal preference I have; you can choose to write or not write semicolons, as per your own tastes.

The other thing we’ve added is some default props, which React requires you store in an object assigned to the static property defaultProps. What are props? They are the data that gets passed in by a parent component, and the child component can then take that data and use it as it sees fit. In a bit, we’re going to modify the App component to do just that, but until then, we’re going to use these default values. It’s also good practice to include default values, as it helps show what props your component is expecting.

Here is a quick explanation of what each prop is for:

Next, we need to add some code that will allow us to render stars. To do this, we’re going to install a font library called FontAwesome, which has thousands of custom icons stored as scalable SVGs. This way, we can style our stars however we want. Specifically, we will be using the react-fontawesome package, which integrates FontAwesome with React.

First, we’re going to install a few libraries via NPM and save them to our package.json:

npm i --save @fortawesome/fontawesome @fortawesome/fontawesome-free-solid @fortawesome/fontawesome-free-regular @fortawesome/react-fontawesome

To summarize, we’re installing Fontawesome, two sets of Fontawesome icons, and a package which provides FontAwesome React components. Once the packages have finished installing, we need to import them into our project.

First, we need to go back to App.js and add a few lines: